Illustration: Katharina A. Wieser / Bureau F

What vine pruning is all about

Once the harvest is over and the grapes are in the cellar, the wine year is finished and the vines go dormant for the winter. Before everything begins anew with budding in the following spring, there is one more step to be taken: vine pruning. In the northern hemisphere, this usually takes place in January and February, when it is cold outside, the days are short and grey – no greenery, no blooming meadows, no chirping birds, and no insects. It is during this otherwise rather unexciting phase of the year that pruning takes place, which is of fundamental importance for the vines and therefore also for the wine. Why this work is done, why it is so important and what the most common types of pruning are – an attempt at an explanation.

The vine

The vine is a climbing plant, a liana, that is constantly searching for objects to help it grow further upwards. Originally, these were other plants such as trees and shrubs. The fruits it bears are eaten by birds or other animals, which distribute their seeds and thus enable the vine to reproduce. As with many other cultivated plants, over thousands of years, mankind has managed to turn these wild vines into what they are today by breeding and crossbreeding. Nowadays, the vines in cultivated vineyards no longer grow with the help of other plants, but almost exclusively either over sticks, wires or both variants.

However, if you simply let the vines grow wildly, it can make cultivation considerably more difficult. A large number of small, sour grapes would be produced, growing further and further away from the vine year after year which are only partially suitable for wine production. So, in order to cultivate wine sustainably, pruning is necessary. Here, the vines, or more precisely a large proportion of the shoots that grew in the previous year, are pruned back, vine by vine. New shoots then form from the buds of the remaining ones, because only these one-year-old shoots develop flowers and thus later also grapes. This is how quality and quantity are determined, because this step determines how many new shoots can develop – which also directly defines the maximum yield later on. This lays the foundation for the wine year and the future of the vine. In addition, pruning influences further growth and the ripeness of the grapes, as well as the vines’ vitality and longevity.

As vines age, there can be major differences in how they are grown. That is why pruning requires a very precise approach – it is a manual task that demands skill and concentration, as the pruning needs to be customised for each individual vine.

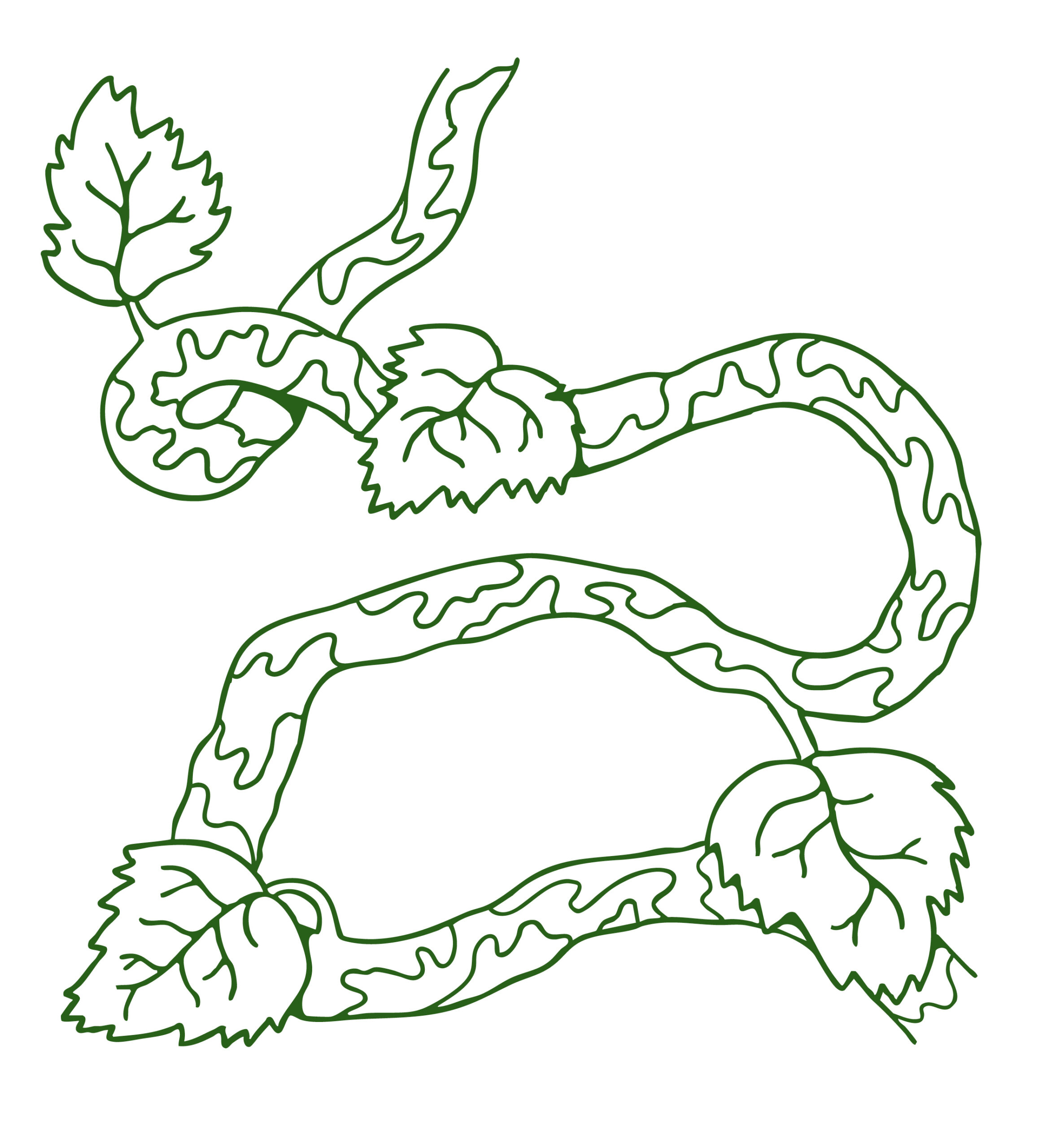

Exactly how the vines are pruned depends largely on the training system, of which there are many different types. These include, for example, training with wires, sticks, both or neither of the two.

Wire-frame training, very common today – also in Austria. Originating in the industrial age, the vines are planted in rows and there are posts at regular intervals with wires put up at different heights for the vines to climb.

Grape variety, climate and soil, which have a major influence on growth and ripening, play just as important a role as vine training. You have to adapt to these conditions, which also form the basis for deciding which pruning method is best suited.

Illustration: Katharina A. Wieser / Bureau F

Gentle pruning

Before we can even get to the different types of pruning, there is one important term that is missing: gentle pruning. In the wine world, this is primarily associated with the name Simonit & Sirch. They are a company from northern Italy that has rethought pruning, written books about it and teaches it at schools, universities and online. In addition, they provide on-site vineyard support for wineries in their vineyards worldwide.

The aim of gentle pruning is to build up and maintain the health of the vine with the right technique, because the wrong pruning can severely impair sap flow and make the vine wood susceptible to disease. Every time the vine is pruned, a wound is left behind, and depending on its size, some of the wood dries out. Therefore, the cuts should be kept as small as possible and their number should be minimized. This results in less dead wood, which helps to keep the sap flow intact and prevents vine diseases. A specific method has been developed to ensure that this remains the case.

Single-pole training or “Stockkultur”, one of the oldest training methods of all, in which the vines grow upwards and are tied to a stick. This has largely been replaced by wire-frame training because the mechanical work in the vineyards is a lot more labour-intensive here, but it is coming back into use and is experiencing a small revival (see also the article in POPCHOP issue one).

The basics of gentle pruning

Initially, it is important to develop a healthy structure. This consists of rootstock, trunk, crown (meaning the upper end of the trunk) and, in the case of certain types of pruning such as cordon pruning, also arms. In this case, arms refer to the shoots that grow from the crown of the vine and become woody and thicker over several years. The development of the structure begins as soon as the vine is planted. The aim is to start forming the trunk and crown over the years and to then gradually build up the arms. Ideally, the wood that grows here year after year should be healthy and intact – the chronology of live wood.

All cuts should be made with the sap flow in mind, which keeps everything alive in the vine. It is important to make the cuts as small as possible, so it is recommended to only cut back one- and two-year-old shoots, as these are usually thinner. This way, the wounds are smaller and can dry out more quickly. It is also necessary to leave “reserve wood”. You should not cut directly at the buds (also known as eyes in winemaking jargon) of the shoots that will later sprout and produce grapes, nor directly at the trunk where the sap is flowing. So you leave a small piece of wood in relation to the cut surface, so that it can dry out without affecting the buds on the shoots and the sap flow in the cane. If you pay attention to all these factors, the vines will grow more evenly, be healthier, more resilient and therefore also more durable. As is well known, old vines potentially produce the best grapes.

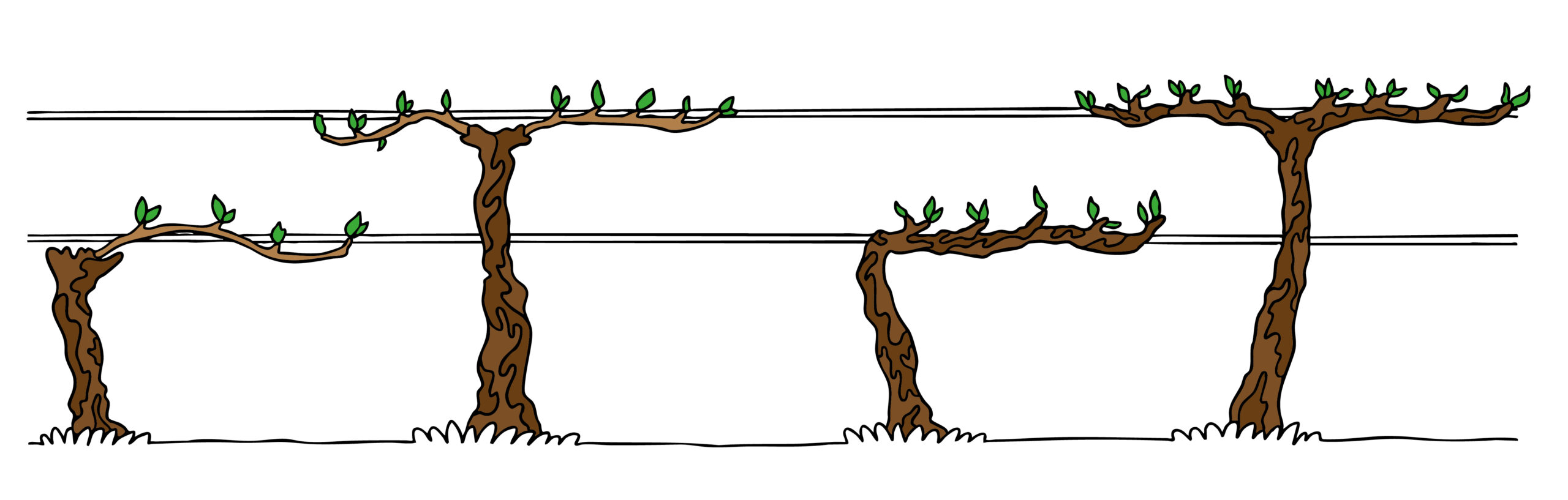

Von links nach rechts: Einarmiger Guyot, Zweiarmiger Guyot, Einarmiger Kordon, Zweiarmiger Kordon

Illustration: Katharina A. Wieser / Bureau F

Cane pruning (Guyot)

Cane pruning using the Guyot method is mainly used in cooler wine-growing regions and is ideal for grape varieties with low to moderate growth, such as Blaufränkisch, because it concentrates the strength closer to the trunk. However, it is important to note that the grape variety alone is not responsible for growth in the vineyard, but also the soils and the water and nutrient supply. When pruning according to the Guyot method, the previous year’s cane and its shoots, which also bore the grapes, are pruned back to one cane and one spur. So one cane remains from the previous year, which is bent over a wire, tied to it and from whose eyes the new shoots will grow, and an additional spur. For the later foliage wall, wires are stretched over it, which the new shoots can climb upwards on, and they are also less likely to break off.

Guyot pruning is divided into two types: single and double Guyot. In the former, there is a cane and a spur; here the vines can be closer together and the planting density is therefore higher. The vines compete for water and nutrients, which results in a lower yield and can lead to deeper root growth. In the double Guyot method, two shoots are bent in opposite directions to form a “T” and each has a spur. Here the vines are much wider, further apart and thus the planting density is lower and the yield per vine is higher.

Pergola, here the vines grow a little higher and cover horizontal wires or stakes, forming a canopy of leaves. South Tyrol is very well known for its pergola cultures.

Spur pruning (Cordon)

When pruning with the Cordon method, an “arm” is built up over the years from the trunk of the vine, which runs along a wire. The shoots grow on this arm and are pruned back year after year to one to three buds on spurs, and then they sprout again and later bear grapes. In addition, wires are put up for the foliage wall. Cordon pruning is used primarily in warmer regions for varieties such as Merlot, since the energy is well distributed over the arms and the growth is better balanced. As with Guyot, a distinction is made between single and double cordon, where the planting density is once again higher or lower.

Bush vines are very resistant to extreme heat, drought, wind or cold and do not require any growth support because the shoots tend to be shorter. They are mainly found in Mediterranean regions or in vineyards at very high altitudes.

With that, the pruning is done for the year. The vines are now bent and tied, if necessary, and the pruned wood is either shredded directly in the vineyard or taken away. When budding sets in, the real work in the vineyard begins – including green or foliage work, plant protection and soil cultivation.

Things can quickly get out of hand here when the weather is warm and humid, the vines grow faster than the vintner can keep up, the risk of fungal disease is high, and you have to keep an eye on the weather around the clock. It feels like you’re constantly playing catch-up with your work, and before you know it, it’s time to harvest again. Once all that is over and the year has been successfully mastered, you secretly rejoice that a somewhat quieter time is beginning again in the vineyards. And now it won’t be long before it’s time to start pruning again.

Weiterlesen